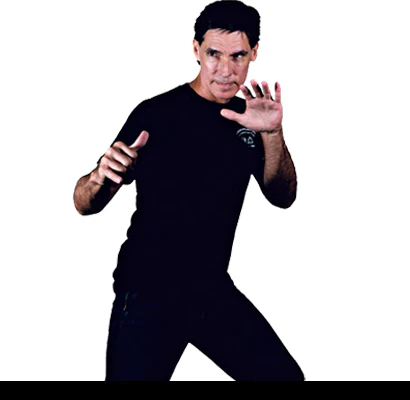

The complete fighter

At JKD Unlimited, we strive to create complete martial artists. This means developing people who are great people, great fighters, and for those who want to share their knowledge, great coaches. A great fighter must be a well-rounded fighter. I don’t want any of our students to have a glaring weakness due to a deficiency in our approach. I want to be sure that each general self-defense scenario has been addressed and trained in a realistic manner. The idea is to hit the entire breadth of martial arts training, and then prioritize those areas that most commonly occur in real situations. Our fighting goal is to:1. Become functional 2. in all the ranges 3. with our without weapons 4. against one or multiple 5. unarmed or armed resisting opponents 6. in a variety of environments. That sounds like a lot, but it is easier than it sounds. By combining the elements into scientific training methods, we see students progress at a very rapid rate. I feel that it is important to follow this outline to ensure that we are not limited in our approach. JKD Unlimited students can fight in the kickboxing range, clinch range, and on the ground. They can use and defend against weapons. They have practiced against the difficult multiple opponent situation, and are ready to use various environmental factors, such as clothing or a barrier, against their opponent. The complete approach is satisfying and a ton of fun. For a more detailed look at some of these elements you can continue reading. Enjoy your training! The following is an outline of the various concepts that guide our training to become a complete fighter. THREE RANGES There are three distances that fights occur in: Kickboxing Range, Clinch Range, and Ground Fighting Range. The longest distance is the Kickboxing Range. This is where kicks, punches, elbows, knees, and head butts can be thrown, but without grabbing the opponent or being grabbed. There is no attachment between the two combatants. Fights often start in this range, and the most common street attack, the big swinging punch, is delivered from Kickboxing Range. The second range is the Clinch. This is where the fight is on the feet, but there is grabbing. It can be a common clinch where an attacker grabs you by the shirt before he starts to punch. It can be as sophisticated as using an Over Hook with a Collar Grab to set up a choke while minimizing the opponent’s ability to punch. The Clinch is where the great majority of takedowns occur. Most throws and takedowns require that you physically grab your opponent in order to gain control over his body and execute the takedown. (Foot sweeps can be delivered from Kickboxing Range.) If you want to avoid fighting on the ground, you must work hard at developing your Clinch skills and at avoiding the Clinch altogether. The last range is Ground Fighting. In a street situation, we usually prefer to avoid the ground. There is less mobility and it is easy for a group of attackers to overwhelm you. I know a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt who was trying to break up a late night street fight. He took a guy down and got the mount on him. The guy on the bottom was panicking and yelling for help, but the black belt just wanted to control him. While he was doing this, another guy ran over and booted the black belt in the head, knocking him cold. He was actually very lucky that the attacker did not follow up and cause serious injury to him, as he was lying there in the street totally defenseless. This is a good example of why we want to avoid the ground in a real fight, but what happens if you were the guy that got taken down? What if you didn’t have friends to help you? If you don’t know how to fight on the ground you will have a very difficult time getting out of the situation unharmed. Real fights often end up on the ground. At JKD Unlimited, we spend a great deal of time practicing fighting from our backs. This is the most dangerous place to be in a real fight, and this is exactly why we practice it so much. Some people say “I don’t want to fight from my back, so I won’t practice all that ground stuff.? I don’t want to fight from my back either, but the more time I spend practicing from those bad positions, the better chance I have of surviving a horrible situation. We practice it because it is so dangerous, much like we practice defense against a knife because a knife attack is life threatening. If you don’t practice kickboxing, you will have a hard time dealing with a good striker. If you don’t practice in the clinch, you will have a hard time defending takedowns. If you don’t practice on the ground, you will not be prepared to deal with a ground fighter. As you can see, just as a striking expert needs to practice in the clinch and on the ground, a ground fighter needs to practice kickboxing. Real fights can move fluidly between ranges, or get stuck at one distance. If long impact or edged weapons are employed, the fight may occur outside of kickboxing range, or within the three ranges. The same holds true for firearms. We must be functional in all the ranges because real attackers usually ambush their victims. In an ambush you won’t be able to choose what range the fight begins in. Your best bet is to be well-trained in each range. NINE TRANSITIONS Fights occur in the three ranges, but there is also movement in between these ranges. These are called Transitions. These can happen by chance, but the skillful fighter will employ transition techniques to guide the fight into the range that he prefers. In a surprise attack you won’t be able to choose which range the fight begins in, but if you can control the transitions, you get to choose which range the fight moves into. There are nine transitions that occur between the ranges in the street self-defense. In Mixed Martial Arts sport fighting, such as the “Ultimate Fighting Championship” and the “Pride” events, there are six transitions. If you start in Kickboxing the fight can transition to the Clinch or it can transition directly to the Ground. If you start in the Clinch, you can move back out to Kickboxing range, or to the Ground. If you start on the ground, you can transition all the way out to kickboxing, or up to the Clinch. In other words, you can move from one range to either of the other two ranges. In MMA sporting events, these transitions are often what the fight is all about. When a great kickboxer fights a great grappler, the first game played is that the kickboxer tries to avoid the clinch or fast takedown in order to keep the fight in kickboxing range. The grappler tries to get to the clinch or shoot in for a takedown to avoid the kickboxer’s strength. If the fight goes to the ground, the kickboxer tries to transition back up to his feet into kickboxing range while the grappler does everything he can to keep the fight on the ground. Whoever controls the transitions controls the fight. Sometimes a great kickboxer will be taken to the ground, but he is good enough on his back that he can defend against the strikes and submission attempts until the grappler begins to tire. When this happens, the kickboxer explodes out of the ground position and to his feet. You then have a fight between a great kickboxer and a winded grappler who doesn’t have the energy to shoot in fast for a takedown. Guess who wins that fight! An important part of our training is playing transition games so that the students can become skillful at moving between the ranges against a resisting partner. Since we train primarily for street self-defense, we also add transitions to a distance which is beyond Kickboxing range: Escape. Since our goal in an actual fight is to go home safely, we must practice creating escape routes from each range. This only comes through proper training, so it becomes part of our transition strategy. This means we add three more transitions on top of those that occur in competition: Kickboxing to Escape, Clinch to Escape, and Ground to Escape. This changes the techniques. In Kickboxing range, you may need to throw punches and circle until you have a clear escape path. This is especially important in multiple opponent situations. If you actually practice going against two people who are fighting back, you will find that it is very difficult to out kickbox them. It is much easier to maneuver your way toward an exit. In the Clinch, a technique like the arm drag can be used to create your escape route, instead of using it to move to the opponent’s back. On the ground you may have reversed your opponent so that you are in a top position. Instead of working to pass the guard or look for a submission, you may prefer to make your exit before his friends show up. Practicing the escape routes in your sparring another aspect that transforms your training from a purely sportive mode into a self-defense mode. This way, you can have it all. So the nine transitions are: KICKBOXING TO ESCAPE KICKBOXING TO CLINCH KICKBOXING TO GROUND CLINCH TO ESCAPE CLINCH TO KICKBOXING CLINCH TO GROUND GROUND TO ESCAPE GROUND TO KICKBOXING GROUND TO CLINCH There are many, many proven techniques that can be used for each transition. It is important to know these, but it is even more important to incorporate these into your resistance training so that you can develop the skill to apply them under pressure. TRAINING METHODS “Knowledge is not power. The ability to apply your knowledge under pressure is power.” This is what it is all about. Not just memorizing techniques, but developing skill in those techniques so that you can use them against someone who doesn’t want you to. Training methods are the essential ways of practicing that will most efficiently develop your fighting skill. Train correctly and you will develop functional fighting skills, no doubt about it. Train poorly and you may be one of those people who knows all about the martial arts, but can’t really fight. Do you want to be a person who can demonstrate an endless stream of techniques, but doesn’t spar well? To me, that is like settling for being a caddy in golf rather than being a player. You carry around the tools of the trade (the clubs), and you know what each one is for, but you can’t actually use them well. If you had good skills you would be playing the game instead of holding the bag. In martial arts we each need to be the one playing the game well. This is not prize fighting, this is real self-defense for an unprovoked attack. If we want to be able to handle a real situation, we must practice in a way that develops fighting skill. The way you train will dictate the level at which you perform. There are two basic types of training methods. One is training with resistance, the other is training without resistance. Training with resistance is a very simple concept. You try to perform your move against someone who is trying to keep you from applying that move. Training without resistance is primarily for memorization of the technique. You may get some muscular or cardio work as well, but the main ideas is to ingrain a certain movement. Examples are doing forms in the air, doing sets on a training apparatus (such as a wooden dummy or heavy bag), or performing techniques and drills with a cooperative partner. It is important for the student to memorize a technique before trying to apply it in sparring. The problem is that most martial artists spend nearly all of their time memorizing techniques with a cooperative partner instead of trying to apply their techniques against an uncooperative opponent. In our classes, at least 80% of the time is spent on Performance Games. This is what we call training where your partner resists your efforts to apply your techniques. There are many Performance Games for each range, each transition, and each position. We have many Isolation Games where we just play with a few particular techniques or positions within the totality of combat so that we can hone those areas. It is important to play the entire game often, with very few restrictions, as this is the closest we can get to real combat in a controlled environment. Of course, we use Progressive Resistance so that each student is playing at the intensity that will best develop their skills. Here is a big question that many martial artists struggle with: How long do you train a student in memorizing techniques before you allow them to play the Performance Games? In other words, how much experience should they have before they start sparring? What do you think? Three years? Three months? We start people playing the game the very first day of training, usually within the first three minutes of training. How can this be? Isn’t it dangerous? Not if you apply Progressive Resistance & Variable Intensity. A brand new student with no training background at all will be shown how to stand in a kickboxing stance with hands up. They will be taught proper mechanics for the jab, and how to cover up against a punch. How long does that take? A few minutes. Then, we pair them with an experienced student or instructor who can control the intensity and we let them play the open hand touch game (touching the top of the head with the hand) using the jab only. They are playing within the first five minutes,safely developing timing, distance, technique, and having a great time doing it. I often see new students who are quite tentative and a little intimidated going into a new activity, especially realistic martial arts training. I see all that drop once they are playing. They smile and laugh as they try to touch their partner while trying to avoid being touched. As the class progresses, they learn the neck clinch with knees, and they learn the rocking chair on the ground. Other techniques are added in too, depending on the particular class. The very first day they get to play Performance Games in each range, so that they begin to develop fighting skills. There is no need to wait years for this. If you do, you will find that the student of three years has to re-learn all the techniques because there was no element of timing, reading, or distancing integrated into the techniques. Only through playing with a resisting partner will you learn to anticipate the moves before they come. There are particular conditioning drills that can be performed as well to enhance the student’s muscular strength and endurance. Hitting focus mitts and using the kicking shields is a great workout and develops good power. Students rarely spar at 100% intensity for safety reasons and to keep the training fun. I believe that unless you are a professional fighter or soldier, the training should be enjoyable. Getting hit at 100% intensity is the opposite of fun. But it is important that each student develops power, and the only way to know that you can hit hard is by hitting something hard. Thus, the focus mitts or kicking shields come out in almost every class. We usually include one to three short rounds per class, but the primary reason for this is to allow the student to strike a target with 100% power and intensity. We make sure that the person holding the mitts does so in a boxing structure, and throws lots of non-choreographed strikes at the student. It will feel a lot like fighting, and is a tremendous workout, but as good as this training is, it still is not quite the same as sparring. The student has to wait for the mitts to be presented to strike, so the flow is not the same. When we spar, we lower that intensity. If you only spar, you may never develop the type of power and the level of intensity that you can through using equipment. The drawback to using equipment is that it is not sparring. Being very good at hitting Thai Pads simply means that you are very good at hitting Thai Pads. While it may develop many attributes, the only way to measure fighting ability is to fight. To recap, the main idea is to train safely, trying to impose your will on a partner who is trying to impose his game on you. You must train against a resisting opponent in order to develop the attributes needed to apply those all so important techniques. TECHNIQUE Techniques are the actual maneuvers you use to affect the opponent. The ability to execute a Technique against an unwilling opponent depends upon your skill, the skill of the opponent, the situation, and the fundamental soundness of the Technique. Most people get sidetracked in their training because they become fixated on learning more techniques. Technique is important, but just because you know 1000 techniques does not mean that you will beat someone who only knows 10. Think about how many techniques there are for defending against a straight punch. Parry, duck, slip, cover, slip and hit, parry and hit, fist destruction, stop kick, stop hit, enter to tackle, etc., etc., etc. There are hundreds of techniques just for a straight punch. BUT, when you are in danger, and an attacker throws a straight punch at you, you only get to choose one technique to defend yourself. At that moment, it does not matter how many techniques you know. All that matters is whether or not you can apply the one technique that you do choose. The same goes in other areas of fighting. You only get to use one move at a time. Most combat sport champions have a handful of techniques that they apply very well. They are probably well rounded, but they have a few moves that they can apply on almost anyone. Don’t get caught up in the “more is better” approach. If you do, you may become a technique collector instead of developing skill. Knowing lots of techniques without the skill is like having a huge collection of automobiles that have no engines. Who cares if it doesn’t work? If you are diligent and train for many years, you can get to a place where you have a wide array of techniques that you can actually use. This takes a lot of training and many years of developing skills in each technique. Some Techniques are simple and just work better a high percentage of the time. These are our basics. Other moves take more coordination, and can become your personal basics over time. On the other hand, people can make up extremely complicated moves that look good against a cooperative partner, but that in reality are virtually impossible to perform against a live, resisting attacker. Here’s the big question: How do we know which techniques to work on first? At JKD Unlimited, we prioritize those techniques that have been proven to work well under the real, stressful conditions of an actual street fight. Do you remember the last time you felt nervous? I mean really nervous. Street fights are so full of stress that our instincts tend to take over. We get that “fight or flight” response. If we fight, we will probably experience a huge adrenaline dump, which is good and bad. Good because you won’t be feeling much pain, and will be able to fight through things that you might not fight through in a class setting. Bad because adrenaline and stress affect our mental and motor skills. We just don’t have the muscular control or the clarity of thought that we do when we are calm. That is why it is so important to practice under stress. You will learn to deal with it better. But, regardless of how well you practice, a real fight has a real threat that cannot be duplicated in a class when you are amongst your friends. Under stress, our motions tend to get wider and more basic. This is why our basics should have as few components to them as possible. This is the concept of Gross Motor Skills versus Fine Motor Skills. If someone had a gun to your head, you may be able to open a door but you would have a hard time repairing a watch. Fine motor skills, as we see in complex martial arts moves, are very, very difficult to perform in a real situation. I once attended a lecture about the ancient Roman warriors, and learned a very important point. Although these battle-hardened warriors were amongst the most successful on earth, the sword fighting combinations that they drilled and used consisted of no more than three movements. No more than three. Why? Because through decades of battles they found that these warriors could not remember more than three moves at a time when under life threatening stress. These were professional soldiers with years of real fighting experience. If these soldiers kept it simple, we need to keep it simple. We work primarily on techniques that require only gross motor skills. Grabbing the neck and throwing knees is a simple gross motor skill that is applied often under stress. Going from an under hook to a slide by double and flowing up to the opponent’s back is a series of moves that can be used if practiced for years. Techniques that require many intricate moves will rarely be applied in real fighting. One exception is on the ground. You can slow the fight down to the point where you can think again and set up advanced combinations. This also comes after years of training, but you first need to become an effective fighter through good. TACTICS Tactics are the strategies we use to implement our techniques. An important concept to consider when developing our tactics is the difference between PAIN COMPLIANCE and INVOLUNTARY COMPLIANCE. Most martial arts techniques rely on pain compliance. This is where you inflict enough pain on the attacker that he decides to comply with you. Hit him hard and he quits. You kick him in the thigh and he gives up. You put him in a wrist lock and he goes along with you. In other words, he feels pain, he decides to quit. The problem here is that it is based upon the attacker’s decision to give up the fight. What happens when you have someone who is very determined and does not want to give up, no matter how hard you hit him? It is hard to make a very determined attacker quit by inflicting pain. It makes some people even more aggressive. If you don’t believe it, ask yourself a question. At what point would you give up if you had to protect your loved ones? Is there any way an attacker could make you say, “Okay, just take my child”? Impossible. You would fight to the death. You would never decide to quit because you were in pain. This is the problem with pain compliance moves. The effectiveness of these techniques is based upon the toughness and will of the opponent. Another common factor is not just toughness or will, but whether or not the opponent can even feel pain. If an attacker is on drugs you can inflict all kinds of damage without making him stop. I have a good story that illustrates this point. A friend of mine named Levi owns a store. He got a call one evening from a worker saying that there was a young man acting very strange who refused to leave. Levi, who has two decades in the martial arts and is very strong, went down to the business. He found a 5’6? man who weighed approximately one hundred thirty five pounds. Not a very imposing guy, especially since Levi weighs in at about two hundred thirty pounds. He tried to coax the man out of the premises, but the young man attacked. Levi fired a strong kick directly to the groin of the attacker. To Levi’s surprise, it did nothing to the guy. The man continued to fight, Levi hit him hard with an elbow, breaking the man’s nose and closing his eye. They guy shot in with a tackle. Levi sprawled, pushing the man to the ground. The guy grabbed Levi’s calf and bit him, causing a puncture wound right through his jeans. Levi pushed away and kicked, driving his shin right through the man’s collarbone. The guy stood up, still fighting. Levi shoved him into the wall, delivered strong knees. Levi heard the ribs breaking. The guy drops to his hands and knees to grab at Levi’s legs again. Levi kicked at him, his hard toed boot landing in the assailant’s teeth. The assailant jumped up, teeth missing, and ran out of the store and up a nearby freeway off ramp. Fortunately, the police had just arrived and caught the man before he got into traffic. Levi called me the next day. He said that he just read one of my articles about going for the choke. My article pointed out that regardless of what someone is on, a well-placed choke will cut off the blood supply to the brain and render them unconscious. No oxygen, no consciousness. Levi understood this, but in the heat of the battle, he did not think of it. Instead, he had a very small guy who was totally battered, but who refused to give up. We chatted about the fact that it is one thing to be aware of a technique and another to actually train it under realistic conditions so that you can apply it under stress. Those all-important training methods made the difference, and you can be sure that Levi now trains chokes diligently. All this leads us to a guiding principle in our tactics. Rather than rely on pain compliance techniques, we want to impose involuntary compliance on an opponent whenever we can. Therefore, the technique that we prioritize over all others is the choke, preferably from the back. If you cut off the blood supply to the brain, the attacker has no choice but to go to sleep. It doesn’t matter how tough he is or if he is on drugs. No oxygen will make him sleep, and a sleeping attacker is not much of a threat. We are always looking for ways to apply a choke. This doesn’t mean that we give up training all the other techniques. On the contrary, we know that a good punch to the head can cause a knock out. We also use all of our striking to set up chokes. If striking ends the fight, wonderful. If not, we are prepared to work our way to a choke and end it that way. It is important to use this tactic in training so that you don’t have to think about it. It becomes instinct because of all the hours of training that you have put in. MULTIPLE OPPONENTS This is a nightmare situation. Fighting one on one is tough enough, but having more than one opponent is extremely difficult for anyone to deal with. This isn’t like the movies where the attackers are professional stuntmen who are paid to make the star look good. This is the real world. Your best tactic is to escape. If you can’t escape, or if you have someone you need to protect, you need to be more aggressive, more skillful, and smarter than the attackers. This is also a good time for weaponry, but I suggest you consult with your local law officials to determine where self-defense crosses over the line to criminal assault. The law in many states says that if you turn the tables on one or more attackers to the point that they are at your mercy, and you continue to inflict damage, you then become the criminal. This is especially true when using weapons against unarmed (or sometimes armed) assailants. The line “better judged by twelve than carried by six” has truth, but another truth is that it is even better to be able to resolve the situation within the parameters of the law. You may not be able to think this clearly during an actual attack, but you can make sure that any weapon you have with you is legal to carry. As with all other aspects of our training, it is imperative that you practice multiple opponent scenarios with resisting opponents. Use progressive resistance and good safety equipment, making sure that nobody gets too wild. We don’t want injuries in training. That said, playing the various Performance Games with multiple opponents will surely open your eyes to the reality of the situation. Let me tell you it isn’t easy. You should also consider that in a street situation you need to be aware of other possible attackers even as you deal with the one in front of you. I know a very good fighter who spent years doing Thai boxing before getting into Brazilian jiu-jitsu. He spent years at this, eventually becoming a black belt. He was at home one night with his friends when he heard a commotion outside. They went out to find a group of men bullying a guy. The friends went over to try to break it up, and sure enough, a melee broke out. My friend clinched with a guy, keeping his hips away like he would in a jiu-jitsu match. He was just trying to calm the situation, but the attacker was going wild. After a bit, my friend snapped out of his sport mode. “I thought, What am I doing? This is a fight.” He tossed the guy to the ground and got to the mount position. The opponent was bucking and flailing around while my friend tried to calm him down. He still didn’t try to punch, but he remembers hearing the opponent scream, “Get this guy off of me.” About that time, the sound of a boot connecting with a skull echoed in the street. My friend lay in a twisted, unconscious heap. Someone had come up and kicked him from his blind side while he was preoccupied with his opponent. Luckily, they did not follow up and he was able to recover without massive injuries. It could have been much worse. In my classes, we add an element to broaden our awareness of multiple opponents. Whenever we play the Performance Games, anyone can break away from his partner and “attack” someone else while they are involved in their sparring session. For example, if everyone is in pairs working the ground fighting, you have to keep an eye out in case one of your friends from across the room decides to run over and make your session a multiple attacker situation. The result is that when we grapple, kickbox, or clinch, we always are on the look out for someone else to enter the fight. This somewhat simulates the idea of being in a real fight and looking for your opponent’s friends to jump in. Of course, it is nothing like the adrenaline and wild environment of the real thing, but it does bring up tactics and a level of awareness that would not be present if we only train the in a more sporting mode. It is loads of fun too! The threat of multiple opponents is also a good reason to practice standing up from the ground. We work this so that we can escape a bad situation, and the ability to stand from the ground is a very important part of our ground fighting training. If you play the Performance Games with multiple opponents, you will see where your weaknesses are. Play safely, but make it as real as you can. WEAPONRY If you get into a street altercation you should always expect to confront a weapon. If someone is bullying you it is because they believe that they have an advantage over you. This could be because he is an experienced street fighter, or it could be because he is hiding a weapon. Think about it. If a person who is smaller than you is giving you a hard time, he may very well have a weapon to back up his words. (It may also be that his “weapon” is the group of friends lurking in the shadows.) Growing up in Los Angeles, I had a group of friends from the roughest part of town. They were great guys, but they wouldn’t stand for being bullied. After a night on the town, they were driving down the freeway at three in the morning when they passed a station wagon with the same number of young men. My friends were big guys who lifted weights diligently while those in the other car were considerably smaller in stature. Somehow looks were exchanged, then gestures, then the small guys motioned for my friends to pull over. No problem. They were ready to fight, especially against these little guys. My friends pulled their car in front of the wagon and were about to get out when one of them noticed the shotgun. One of the small guys had just pulled the scattergun out from under the seat. My friends dove back into their car and high tailed it out of there. Of course, they should have just ignored the whole thing in the first place. Who cares what someone else says about you. But, being young and impetuous, they almost walked into a tragic situation. If they had been expecting a weapon, they would not have pulled over. There are three basic types of weapons in common street usage today: 1. Impact weapons, such as sticks, clubs, bottles. 2. Edged weapons, such as knives, razors, broken bottles. 3. Firearms, from small pistols to shot guns. In class, we concentrate on dealing with impact and edged weapons. I encourage my students to work on firearms training outside of class. If we don’t practice with weapons we will be at an even bigger disadvantage if we have to face one in the street. Just as with the empty hand skills, I am not talking about forms and drills. For self-defense purposes, you have to practice fighting with and against them to develop usable skills. That uncooperative training partner is your best friend if you want to really be able to fight with weapons. We use progressive resistance and variable intensity in our weaponry work. We mainly practice empty hands against knife or stick, but we also do knife versus knife sparring and stick versus stick sparring. There are many combinations you can use, but because of time constraints, we concentrate on these fundamentals. Realistic firearms training should also be done with progressive resistance, but never to full resistance! Best to put on approved protective equipment under the supervision of a certified trainer and see what you can do against a gun using paintballs or “simunition”. This way you will know if you moved in the right way at the right time. If you didn’t, that welt will motivate you to move a little quicker. When it comes to shooting, target practice is okay, but it is much like practicing martial arts with a partner that just stands there for you. Everything changes when the opponent is fighting back, or in the case of firearms, shooting back. Methods that work well on the shooting range when you can get into your solid stance, regulate your breath, focus on the front site, and slowly squeeze the trigger have been proven to be almost useless in a surprise gun battle. As video cameras become more and more ubiquitous, we will have even more proof that under pressure most people crouch, square off toward the threat, and focus on the danger. No sideways stance, no upright position, no focusing on the front site. This is simply reality. There are times when target shooting type methods work very well, but in surprise attacks your instincts tend to take over. Just as in our empty-handed training, just because something works well in a sterile environment DOES NOT mean that it will work in the stressful, pressure packed situation where your life is suddenly on the line. Like all of our other training, we must do our weaponry training in an environment that comes close to simulating a real situation while maintaining safety. ENVIRONMENT Your techniques and tactics must change to accommodate the environment that the fight takes place in. By environment I mean anything around you that can affect the fight. Most people practice martial arts in a beautiful but sterile environment. Nice, flat flooring, mats, no obstacles, and good lighting. Most real fights take place in low lighting where you are surrounded by obstacles. You see the problem. If you don’t practice in the environment that a real fight takes place in you may be forced to improvise something that you have never practiced while in the midst of combat. There will be enough adjustments to make in a real fight without having to wing it on environment. Remember also that environment can work against you, but you can use it in your favor. The most common environmental considerations are clothing and barriers such as walls, cars, tables, etc. Almost anyplace you could get into an altercation there will be clothing involved and there will be a wall or other barrier around. Now if you get into a fight on the fifty-yard line of a football field against a naked attacker, well, I’ll let you sort that one out for yourself. For most of us, a real situation will happen with clothes to grab and obstacles to bump into. People tend to grab at each other’s clothing in the clinch. You can often tell which guys have just been in a fight because they usually have their shirts torn. If you are wearing a jacket the attacker can use it against you by grabbing it and yanking you all over the place. If you have practiced well, this will not be a large problem. You will be able to keep your balance and start your counter attack because you have dealt with the situation in training. This is why we sometimes wear sturdy clothes such as a judo or jiu-jitsu uniform during practice. You need to be experienced in dealing with a strong grip on your clothing. At the same time, you learn how to use the opponent’s clothing against him. The only choke that can be done standing while facing the opponent is the collar choke, usually performed while pinning the attacker against a wall. There are certain throws that work by using the adversary’s clothing. Many of these are from judo, and let me tell you these can be executed very quickly. Developing the skills to use the clothing against an attacker can make all the difference in a real fight. The barrier, be it a wall, fence, or car is another environmental consideration that can be used against you or in your favor. Dealing with the barrier is so important that I have dedicated an entire section to it. Let me just say here that you can use the wall to go from very bad positions to good positions. You can also use it to aid in takedowns, to nullify submission attacks, or to set up striking. If you don’t have this as part of your normal training, I suggest that you add it right away. Other environmental considerations include the light level, slope and slickness of the ground, and the evenness of the surface. If your punch defense relies on a split second determination of whether it is a straight or curved punch, you are going to be out of luck in a low light environment. That is why I teach the “cover” defense first, as it works against almost any attack to the head without the necessity of seeing which particular strike is coming. Slope is important because if you like to sweep people to your right, but your right side is facing up hill, you are not going to be able to sweep well. It is hard to throw up hill, so you need to be ready to turn an opponent to put him in position. If the ground is wet, muddy, or icy certain techniques are out the window. I was told that there is a style of fighting in the Southern Philippines where the practitioners immediately fall to the ground to start the fight. The region has so much rain that the ground is always muddy, so might as well start on the ground in a position of your choosing rather than slipping and falling in an awkward position. An uneven surface provides unique challenges as well. If the ground were littered with rocks you would not want to fall to the ground at the first sign of danger. You would not be able to move lightly on your feet either. Environment can dictate the fight, so best to practice in various environments when you can. If nothing else, use the clothing and barrier in your training, as those are the most common environmental factors. If you want to be prepared, you have to practice in as many situations as you can. USING THE BARRIER Barriers are everywhere in real fights. In the training hall, we usually have wide open spaces to make training easier and to ensure safety. The real world environment consists of walls, tables, cars, dumpsters, and fences. The barrier can be your best friend or it can act as a second opponent. It is imperative that you train with the wall as a factor so that you can use it to your advantage. All of the chokes performed in the clinch are easier to apply if you can back your opponent into a wall. The less the opponent moves, the easier it is to finish the choke. It is also harder for the adversary to throw strong punches when he is stuffed against the barrier, but you must first get the opponent’s back to the wall. The basic way to move the opponent to the wall is by the old push-pull routine. If you are facing the wall, and you have the neck clinch on the attacker, you can start to pull him forward. If he resists, which is likely, you can use his momentum to drive your elbows into his chest and push him straight back to the wall. If the attacker is facing the barrier, or if it is to your side, you will have to twist his head and turn him so that his back is toward the wall before you run him into the barrier. The same method applies if you are clinching on his body. You need to get some momentum going so that you can guide the attacker backwards into the wall. Once you have his back to the wall you need to keep him there. There are two key elements to achieve this: forward pinning pressure and blocking his ability to move to the side. You need to pin his upper body against the wall with your arms, shoulder, or chest. Your head may come into play as well. The exact method you use will depend upon the particular clinch position you are in. If your left arm is over hooking his right arm, you need to also control his other arm. You can have your right arm underhooked under his left, or you can block his left biceps with your right hand. You pin him with your chest and head as you set up your collar choke. To keep him from sliding out to the side, you need to put one leg deep between his. (You can also add knees to the groin here, but if he is feeling no pain you want to utilize maximum leverage to keep him pinned.) Putting your leg deep between his creates a barrier so that he cannot simply move to the side and get his back away from the wall. He will have to actually step high over your leg to do move out, which is very difficult to do when pinned. As with all other techniques, you need to spend time playing the game of putting your partner’s back to the wall, playing the game of keeping him there, and playing the game of finishing the choke in order to develop your functional skills. Another great advantage of using the wall is that it makes getting a takedown much easier than trying to do it in an open area. There are times that it is to your best advantage to throw the person to the ground in order to finish the choke. This depends upon the situation and your personal level of ground fighting skill. Using the wall can facilitate your takedown as it takes away many of the attacker’s counters. The first counter to the bear hug, single leg takedown, double leg takedown, and many reaping throws is for the opponent to move his hips and legs back away you. This is called a sprawl in wrestling and is the first takedown defense learned. By putting your opponent against the wall you take away his ability to sprawl his hips and legs back, thus making your takedown much easier. This is not a book on takedowns, but I want to at least share one simple move that has been used effectively in cage fights for years. One of the most efficient takedowns against the wall is to first get your arms underneath those of your opponent in a bear hug position. At the same time you put one leg forward deep between the opponent’s legs while driving him to the wall with your shoulder. Having your leg deep makes it very difficult for him to move right or left. Your head should be up against his chest, not down under his arm where you are susceptible to the guillotine. Once in position, quickly drop down, while maintaining good posture and pressure, to grab behind his knees with both hands. Drive with your legs to push up and in with your shoulder to keep him pinned against the wall with an upward pressure. Pinning him upward into the wall takes a lot of weight off his legs, making it easy to lift his legs up and away from the ground. By keeping forward pressure, you can land the attacker in a crumpled heap against the wall. You now have space to escape or attempt to finish the fight. With practice this takedown can be done very quickly, giving the opponent very little time to mount any sort of counter. He will be down before he knows what happened. Bear with me as I emphasize again that the key to developing usable skill is to actually practice against the wall with a resisting partner. You will want to spend time practicing getting your partner’s back to the wall, then pinning your opponent to there so that he does not slide out easily. This Performance Game is loads of fun as both partners jockey for position. Train this for a month and then try it against someone who has never played the game. I’ll bet that you will be surprised at how easy it is for you to get your new partner’s back against the wall and keep him there. If you have a proper padded surface and know how to fall safely, add the takedown into the game. Be sure to take care of your partner when you take him down. Now put on a jacket and play the game while trying to get to the collar choke. Developing skill against the wall can be a huge advantage in a real situation. It is like having a friend who is always there to help you.Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.